Bibliography:

Baily, G.A., Pamela M. Jones, Franco Mormando, Thomas W. Worcester, ed. Hope and Healing: Painting in Italy in a Time of Plague 1500 – 1800. Clark University, College of the Holy Cross Worcester Art Museum, distributed by the University of Chicago Press: 2005.

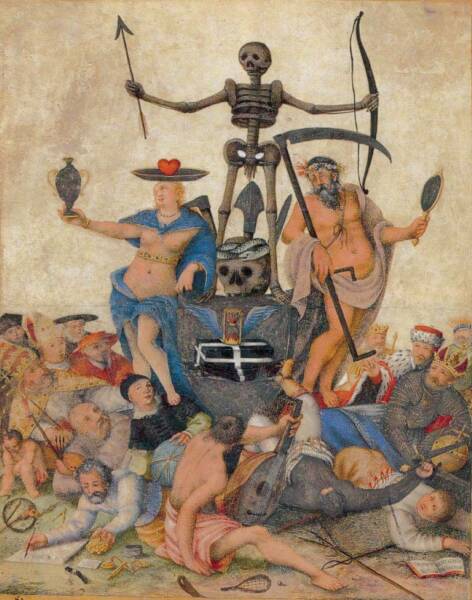

Boeckl, Christine M. Images of Plague and Pestilence: Iconography and Iconology. Missouri: Truman State University Press: 2000.

Davidson, H.R.E., and W.M.S. Russell, eds. The Folklore of Ghosts. Cambridge: Folklore Society, 1981.

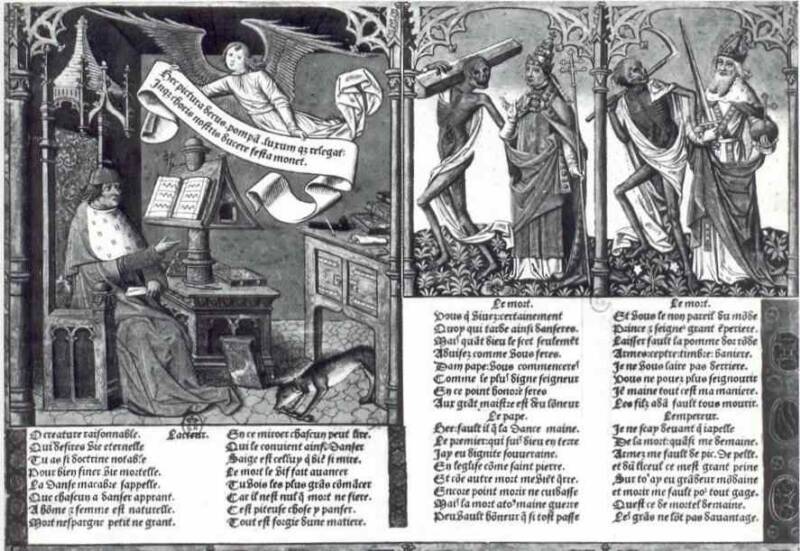

Dance of Death: Printed at Paris in 1490. A reproduction made from the copy in the Lessing J Rosenwald collection, Library of Congress. n.d.

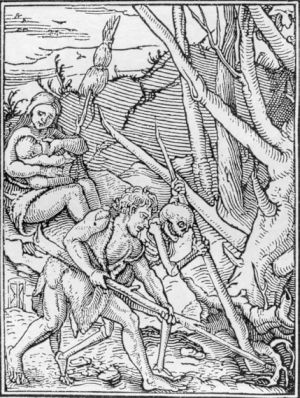

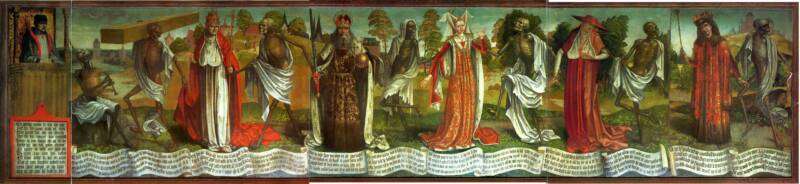

Death and the Visual Arts. New York: Arno Press, 1977. Contains: Clark, James M. The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Glasgow, Scotland, 1950. And: Leassing, E. How the Ancients Represented Death. (Reprinted from Selected Prose Works of G.E. Lessing, Translated by E.C. Beasley and Helen Zimmern, Edited by Edward Bell). London, 1879.

DuBruck, Edelgard and Barbara I. Gusick, ed. Death and Dying in the Middle Ages. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1999.

Eichenberg, Fritz. Dance of Death: A Graphic Commentary on the Danse Macabre Through the Centuries. New York: Abbeville Press, 1983.

Finucane, R.C. Ghosts: Appearances of the Dead and Cultural Transformation. New York: Prometheus Books, 1996.

Gundersheimer, Werner L., Introduction. The Dance of Death By Hans Holbein the Younger: A Complete Facsimile of the Original 1538 Edition of Les simularcheres & histories faces de la mort. New York: Dover Publications, 1971.

Hole, Christina, E. and M.A. Radford, eds. The Encyclopedia of Superstitions. USA: Helicon Publishing, 1961.

Irvins, William, ed. The Dance of Death: Printed at Paris in 1490. A reproduction made from the copy in the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Library of Congress.

Maser, Edward, trans. Cesare Ripa: Baroque and Rococo Pictoral Imagery: The 1758 – 60 Hertel edition of Ripa’s “Iconologica” with 200 Engraved Illustrations.” New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 1971.

Matthews, Roy T. and F. Dewitt Platt. The Western Humanities: Volume I: Beginnings Through the Renaissance. 5th ed. Michigan State University: 2004.

“Medieval Sourcebook: Bocaccio: The Decameron - Introduction,” http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/boccacio2.html, as retrieved on March 9, 2004. Translation from: Boccaccio, The Decameron, M.Tigg, trans. (London: David Campbell, 1921), Vol I. Pp. 5 - 11. Website © by aul Halsall, Jan. 1996.

Musacchio, J.M. “Weasels and pregnancy in Renaissance Italy.”Renaissance Studies Vol 15, No. 2. Oxford University Press: 2001, pg. 177.

Warren, Florence, ed. The Dance of Death. London: Oxford University Press, 1931.

Warthin, Scott A. The Physician of the Dance of Death. New York: Arno Press, 1977.